China is pulling a fast one on western nations and it is about time we called them on it.

For example, on July 24th , representatives from the EU and China met at a summit in Beijing to discuss their plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Both nations reaffirmed their commitment to the Paris Agreement on climate change and urged greater emission cuts, promotion of “green technology,” and a call for strong action at the COP30 climate summit coming up in Brazil this November.

But is the west being “taken for a ride” on all this? Is China really committed to overhauling their coal-powered economy with so-called green energy?

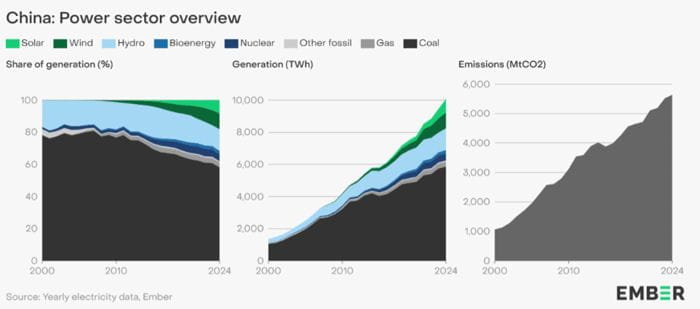

Although China has significantly expanded its solar and wind power capacity, the following graphs show that it is still heavily reliant on coal. This is why its greenhouse gas emissions have soared and now stand at double those of the US.

As of 2023, China was the world’s biggest emitter of carbon dioxide emissions at 35% of global emissions. While Chinese politicians tout their increased reliance on solar and wind to reduce the country’s “carbon footprint,” they are continuing to build coal power plants at a breathtaking rate. In 2024, they began building 94.5 gigawatts (GW) of new coal-power plants and resumed 3.3 GW of suspended projects in the country. This was an all-time high in the past ten years. In 2024, it permitted more coal capacity than the rest of the world combined.

Moreover, they are continuing to construct and finance coal plants in African, Southeast Asian, and South Asian countries. Although they have committed to halt the introduction of new coal plants overseas, existing plants or those that are in use will continue to run. India is the recipient of most of China’s overseas coal production.

So China’s renewable energy claims are just smoke and mirrors: coal use is expanding and most of their increased production of renewable energy technology is being built using coal as the energy source.

One point of tension at the July summit was that China wants tariffs revoked on its electric vehicle (EV) exports to the European market. China is booming in the EV market, which understandably raises concerns for domestic EU EV production. Concerning the restrictions of Chinese exports into the EU market, President Xi said:

“We hope the EU will keep its trade and investment markets open, refrain from using restrictive economic and trade tools and provide a good business environment for Chinese companies to invest and develop in Europe.”

China’s expanding share in the European EV market threatens European nations’ ability to grow their own green technology sector. Businesses and millions of EU auto industry jobs are at risk, as well as millions of other jobs related to EV production. With the EU remaining as China’s largest export market, these issues have created tensions between the countries despite their joint affirmation of climate change goals. No firm agreement was made about the issue of trade at the late July summit.

Hybrid cars from China are able to enter the EU levy-free, so the PRC have responded by introducing more hybrid models in Europe. The future of electric and hybrid vehicles is anything but certain, but it is clear that it is not in the best interest of the EU to rely on Chinese vehicle production while their own manufacturers struggle to stay afloat.

Moreover, the minerals crucial to EV production are mined by China with little or no environmental or human rights concerns. The lithium-ion batteries used in EVs are primarily composed of cobalt, lithium, manganese, and graphite, which are mined in developing countries. For instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo provides about two thirds of the global output of cobalt. Congolese mines are controlled by Chinese companies which employ child labour in extremely dangerous conditions. For more details on these issues, see “Wind and Solar are the Most Environmentally Destructive Energy Sources” that Dr. Jay Lehr and I wrote in 2021.

China has agreed to create an updated supply mechanism for their exports of critical minerals, which is further concerning due to their poor standards in mineral extraction. Even in their domestic EV production, the EU relies on these minerals from China, and so continued dependence on China’s minerals will only worsen human rights and environmental abuses.

To understand how China gets away with all this we need to examine the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which is the governing document for all UN climate agreements, including the Paris Agreement. Article 4 of the UNFCCC states that the first and overriding priority of developing nations is poverty alleviation and development. Since China is still considered a developing nation under the UN’s climate agreements, and burning coal is the cheapest way to continue to pull their people out of poverty, China will burn all the coal it wants indefinitely as it has full rein to soar past its Paris Agreement target to cap emissions by 2030.

When Xie Zhenhua, the Chinese climate negotiator at COP 20 in Lima, Peru (2014), was asked about China’s exemption from binding emissions reductions under Article 4 of the UNFCCC, he simply pointed to the article and said:

“We are exempt. We are a developing country.”

He then explained that the purpose of the Paris Agreement, then under development, was to enforce the UNFCCC, not to replace or change it.

So China knows it has a sweetheart deal—they can expand their coal usage, build coal stations across the world and grow their emissions without limit while boasting that they are following international climate agreements. All the while, they make a fortune selling wind and solar power equipment and batteries to western nations riddled with guilt over our own emissions that we falsely believe are damaging the climate.

China’s climate strategy is a strategically brilliant confidence trick—an elaborate balancing act in which the country presents itself as a global leader in clean technology, while approving and constructing coal-fired power plants at a staggering pace. It’s high time we called them on this.

Note: Mary-Jean Harris, BSc, MSc (physics), contributed to this article.

- GUEST POST